How do we get to know bodies with children in early childhood education?

Over two years, we – early childhood educator co-researchers, preschool-aged children, and a researcher – have been investigating how everyday practices, priorities, and perspectives in early childhood education shape how children get to know (and do not get to know) human bodies through particular logics and relationships in one early childhood education program in Toronto, Canada.

Titled Working Toward Postdevelopmental Fat Pedagogies in Early Childhood Education in Canada: Nourishing Pedagogical Relations Beyond Fatphobia, our project was rooted in an intention to cultivate more just relations with fat in early childhood education by wrestling discussions of fat and bodies out of the disciplinary limitations of child development, obesity discourses, and healthism – and into the life-making purview of postdevelopmental pedagogies. We worked with a pedagogical inquiry research methodology to study, respond to, and create practices for getting to know bodies and fat outside of status-quo approaches.

We have organized the ‘guts’ of our project into six bundles

As you scroll down, each bundle - each cluster of the guts that keep this project alive - will appear.

Within each cluster, there are connections/links that detail questions, concerns, or stories.

We share our work in this way, on a single common page without an overarching ‘menu’ that allows independent access to each section, because we want the project’s guts and bits and clusters to be joined - articulated - alongside and through one another.

A menu that picks the project’s skeleton apart cannot, we suggest, draw us into thinking bodying pedagogies that are complex, emplaced, and held together with these stories, these commitments, and these questions.

Sketch/Skeleton/Summary

We ‘do’ bodies with children: living with bodies is an ongoing activity in ECE

Our initial three intentions

Recognizing bodies

Figuring out bodies

How do we get to know bodies with pedagogy?

How do we get to know bodies with children in ECE?

How might we continually work at co-creating and sustaining more livable - emplaced, fleshed, responsive, affirmative, and ever shapeshifting - bodying relations with children?

Our context, concerns, and inheritances

Body pedagogies and biopedagogies

Body curriculum

Normative child development.

Bodying

Bodying and relations

Bodying and subject formation

Bodying pedagogies

Imprecise body grammars

Escapable body temporalities

At the heart of this project is the assertion that living with bodies is an ongoing activity; we ‘do’ bodies.

Bodies are not inert, invisible, or unchanging, and our experiences with bodies cannot be universalized, suspended, or finished (Anastasiou et al., 2018; Azzarito, 2019a; Mol, 2002; Lenz Taguchi et al., 2016). As we continually ‘do’ bodies, we inherit, interrupt, create, and nourish specific relationships with bodies and we draw on the knowledges that make bodies make sense in particular relations (Evans et al., 2008). Getting to know bodies is a collective but situated project, as bodies come to matter within the traffic of navigating complex everyday worlds (Merewether et al., 2024; Powell & Somerville, 2022). Knowledges, discourses, subjectivities, publics, inequities, and governance articulate a vision of the ‘good’ body within a context, naming how and why bodies are desirable or devalued and, accordingly, how we should relate with bodies to obtain and maintain prevailing images of the ideal and normative body (Deng et al., 2024; Leahy et al., 2015; Powell & Fitzpatrick, 2015).

When we inaugurated this project, we wanted to focus specifically on children’s relations with fat, fatness, and anti-fat bias.

We began with three intentions:

(1) Trace how and why children and educators form particular relationships with fat, paying attention to how the practices, politics, and pedagogies that ‘make’ fat are complicit in overarching systems of ongoing settler colonialism, white privilege, and neoliberal subject formation;

(2) Work collaboratively to critically examine existing pedagogies related to fat, noting how they thread through seemingly innocuous everyday practices;

and (3) Support local pedagogies that make space for doing children’s relations with fat, along with pedagogical commitments concerned with justice, equity, collectivity, and living well together into the future.

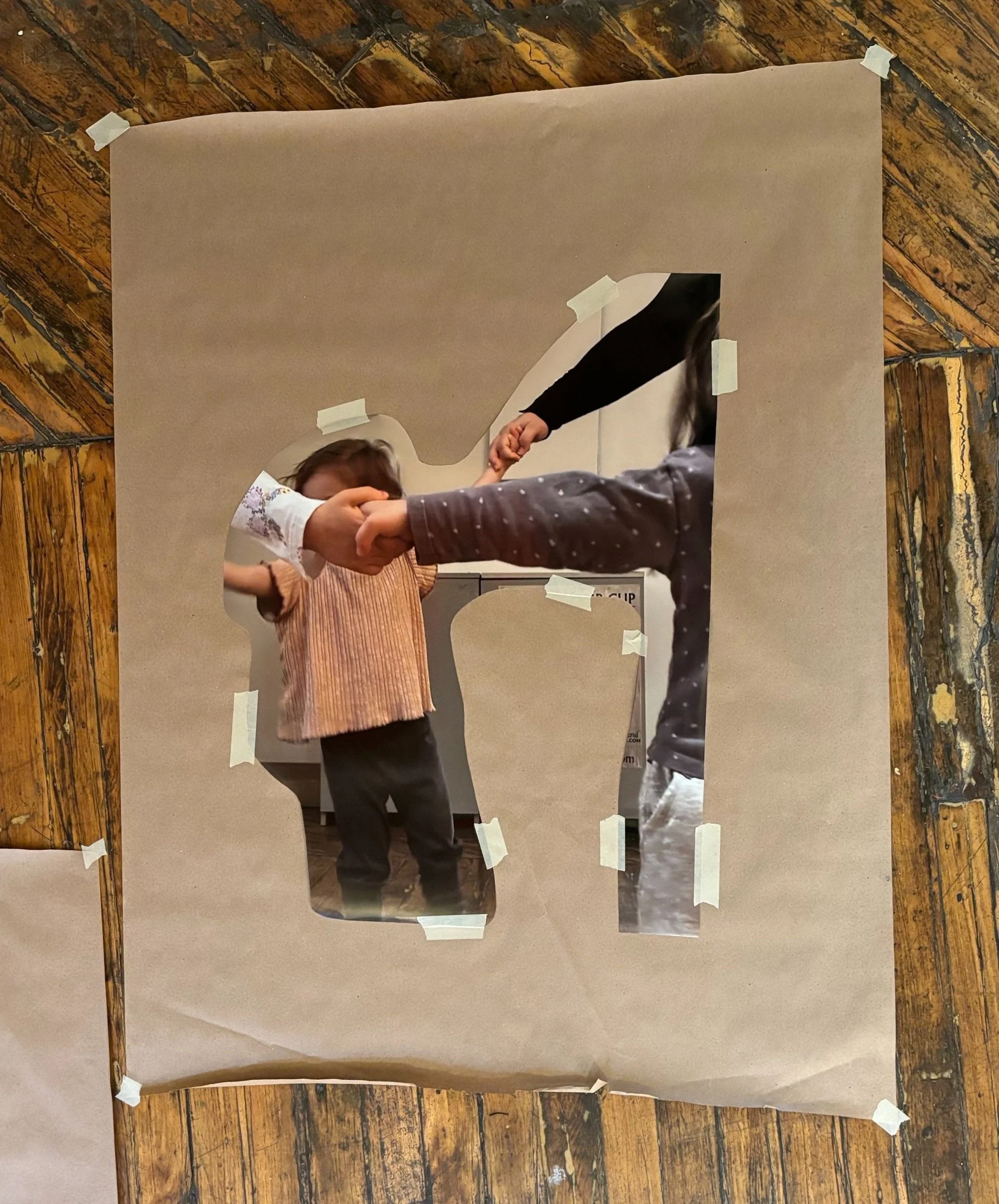

Early in this project, we worked with two practices: recognizing bodies and figuring out bodies.

How do we get to know bodies with pedagogy?

As we worked to craft practices for sustaining our intention to recognize bodies and figure out bodies with children, we chose to stand firm in holding bodies as an unapologetically pedagogical undertaking: how we get to know bodies, fats, and muscles is acutely tangled with how we get to know the uneven, shapeshifting, and ongoing work of creating a life together. Thinking alongside Vintimilla and Pacini-Ketchabaw’s (2020) discussion of how “pedagogy thinks, studies, and orients education, including its purposes, protagonists, histories, relations, and processes” (p. 630), our grounding intention for the project began to shift. As we studied how possibilities for recognizing and figuring out bodies are shaped by anti-fat discrimination rooted in neocolonial body politics, we continually bumped into questions of how bodies and pedagogies are made knowable through processes of reciprocity, correspondence, and exchange that invent and re-invent bodies and pedagogies, and that become meaningful within situated, lively commons. The logics, relationships, imperatives, and accountabilities that inform how we understand bodies nourish and are nourished by the logics, relations, imperatives, and accountabilities that elaborate our lives – including what is forgotten, silenced, taken-for-granted, refused, remembered, imaginable, and not-yet-known.

Answering to these knots of bodies and pedagogies, our intention became more abrupt and more slippery: how, we asked, do we get to know bodies with children in early childhood education?

Wanting to follow this ‘problem’ of how bodies and pedagogy infiltrate one another and co-articulate lived conditions, we spent time with Vintimilla and Pacini-Ketchabaw’s (2020) proposal that “becoming ever more attuned to the conditions of our times forces us to be inventive and imaginative” (p. 636). That our work of getting to know bodies with children must also be speculative and propositional required that we name a second revised intention: how might we continually work at co-creating and sustaining more livable - emplaced, fleshed, responsive, affirmative, and ever shapeshifting - bodying relations with children?

Our approach to studying how we get to know bodies with children contends that that bodies – muscles, tendons, nerves, hormones, and skin – actively contribute to shaping possibilities for, and untenable in, everyday life in early childhood education.

With time, we elaborated on these two questions and named particular iterations or extensions important to our context.

These supporting questions intentionally begin with the preposition ‘if’, as we want to notice how each question requires a leap of faith from the status-quo. This means that we are not using ‘if’ to mark a hypothetical scenario or an abstract thought experiment. We use ‘if’ to emphasize that getting to know movement beyond taken-for-granted understandings requires intentionally figuring bodies beyond a singular universal experience/truth/definition and that different relations with bodies make visible different concerns, tensions, interruptions, and possibilities. The ‘if’ highlights that we constantly make choices, in dialogue with contexts and inheritances, about how bodies can and cannot be understood in early childhood education.

Our Context, Concerns, and Inheritances

Holding that bodies and pedagogies are entangled, we think alongside a rich collection of critical scholarship and activism that analyzes (and stirs up meaningful trouble for) how dominant knowledges, relations, and structures legitimize particular bodies and moderate body logics. Contemporary taken-for-granted relations with bodies are never accidental, inherent, or immutable natural/biological matters. How we get to know bodies is a non-innocent, highly consequential practice that takes shape in a social context. Because any particular context also informs subject formation, power dynamics, and the organizing logics of a public, prevailing body relations echo systemic valuations of morality, agency, citizenship, and personhood.

Noting what becomes possible and impossible for getting to know bodies with children within this constellation of body logics and relations, subjectivities, systems, and pedagogies is, in our project, the ethical impetus for our work. We study bodies in a context of non-innocence, inequity, and oppression, and are concerned with the livability of particular modes of ‘doing’ bodies.

We emphasized three concerns we wanted to interrupt in our context - ECE in Canada - (1) body pedagogies and biopedagogies; (2) body curriculum; and (3) normative child development.

Bodying

Alongside studying how our contexts, concerns, and inheritances that shape how we get to know bodies with children in ECE, we chose to foreground the lively, cascading labour of ‘doing’ bodies; if bodies are an activity, how might we attune to, interrupt, and incite body-making activities towards creating more livable body relations with children? Vital to how we chase this question of doing bodies is a recognition that this requires more-than-curricular or mechanical substitutions, where our proposal for bodies as activities reaches through the layers of our work and reconfigures our anchoring question of how we might get to know bodies with children in ECE. Put differently, when we take seriously that we do bodies with children, we need to risk inherited and dominant structures that conceptualize bodies as passive mediums used to stage human sociality and intellect, as biologically determined, and as ethically or politically neutral corporeal and material realities (Fullagar, 2020). This means that doing bodies otherwise with children cannot be addressed by only changing the discourses or approaches used to understand bodies (ex. adding mindfulness activities) or only by integrating analyses of power, oppression, and difference to recognize how bodies are political and ethical (ex. adding body positivity content). Doing bodies is, instead, a question of how bodies make and are made, over and over, with subjectivities, pedagogies, and relations that do not suspend – and are not disconnected from – these activities in the name of predictability or stability (ex. developmentalism’s child), identity or subjecthood (ex. the self-responsible neoliberal individual), biosocial essentialism (ex. healthism, medicalization), or human exceptionalism (ex. bodies as completely knowable). This is not a move to improve activities that impact existing understandings of bodies, but instead to grapple with how doing bodies disrupts how we understand and are made understandable with bodies (Ivinson & Renold, 2021; Rice et al., 2021).

We think with Manning’s (2014) articulation of bodying, where “body is always a verb, an activity of bodying, a becoming-active of the paradoxical tendings – the disequilibriums, the multiple balances – that incite it to co-compose, dynamically, relationally, with the world” (p. 178). For Manning, movement – worldly dynamisms and forces that spur and overflow possibilities for events and forms – produces a body. Movement, here, is resolutely incomprehensible to technocratic logics of movement as travel/motion, representation, sensorimotor integration, or an individual body’s performance. When “a body never pre-exists its movement” (p. 164), bodies cannot become perceptible, experienced, or occasioned outside of lively situated processes of movement that tend to (and trouble) how a body momentarily takes form. Bodying, cohered with movement, is eventful; it is palpable and generatively unstable, where “this singular form-taking is but a phase in the wider realm of movement-moving; it is its capacity to dephase that makes it movement” (p. 172). In our research, as we work at getting to know bodies in more livable ways with children, bodying emphasizes the high-stakes precarity of how – forces, fields, processes, attunements, habits – we get to know bodies in ECE. Bodying amplifies the problem of how we get to know bodies with children when the body is not a starting point for encountering worldliness: how do we get to know bodies when dominant ECE paradigms or practices for knowing a “preconstituted body” (Manning, 2016, p. 94) deliberately delimit what is possible and impossible for this ‘how’? Perhaps even more pressing is the problem of how we get to know bodies otherwise with children when ECE (as an iteratively tangled structure and a collective) persistently reiterates methods for knowing bodies that “tend to dwell in within the realm of the already imaginable” (p. 92), isolating the body from events of speculating, experimenting, and inventing.

Importantly, bodying is never abstract nor hypothetical for Manning (2014). Bodying happens with tendencies and thought and inheritances and speculative futures, but these context-forming, world-making forces are energetic and generative, not deterministic or docile. “A body”, Manning (2016) contends, is a “tentative construction toward a holding in place” (p. 94) where place and bodies, and the relations and materialities and forces that enliven their forms and unravellings, collide to “activate a bodying not yet defined” (p. 95). In our research, meeting bodyings as unstable events within and of a shapeshifting world asks us to recast how we study and respond to habitual, well-patterned, already knowable bodies. Manning elaborates how “a body is field-effect in a complex relational milieu that includes the sense of its limits – a body-envelope – but in no way stops there” (p. 133), and the possibilities that a body ‘in no way stops there’ reminds us that bodying is a process at-stake. How we get to know a body here, now, is not an inevitability; it matters and is deeply consequential for everyday life, and when bodying is processual, the possibility for inciting alternatives holds. We also take seriously that not-yet-familiar bodyings are not inherently liberatory or affirmative and while bodying is generative, there is no promise of bodying a more just world. Put differently, this underscores that as we work at getting to know bodies otherwise with children, we need to cultivate a situated and collective active diligence that notices how power, normativity, and exclusion compose across, circulate through, and are made and re-made with (our, these) bodies.

Accordingly, bodying asks us to tend to how everyday acts of abstraction, excision, subtraction, and dissection implicate us in wondering “what else does that mean we don’t see” (Manning, 2016, p. 99). Further, because movement composes and infiltrates the temporary bundle that is a body, “total movement is why no form can ever be reproduced, and why no body can pre-exist the event of its bodying” (Manning, 2014, p. 169). When a body is not made to exist external to its movement, the reductions, extractions, and violences that lend bodies stability and certainty in ECE become visible, felt tangibly in their cleaving of bodies (both child and adult) from movement’s activities and excesses. As we work to think bodying with pedagogy, we take up two more particular threads of bodying: relationality and subjectivity.

Bodying Pedagogies

In our work, we propose that bodying – with relations, commons, subjectivities, inheritances, presents, and futures – becomes tangled with pedagogies with moving, in verbing, as activity. Bodying pedagogies are, in our work, moves into figuring out how to get to know (to do, to body) bodies pedagogically, where “pedagogy thinks, studies, and orients education, including its purposes, protagonists, histories, relations, and processes” (Vintimilla & Pacini-Ketchabaw, 2020, p. 630). Bodying pedagogies study, respond to, interrupt, and transform how we do bodies with children and, therefore, do not necessitate that we negotiate with or preserve dominant body logics (ex. child development, healthism) and body relations (ex. control, morality) in ECE. Following Vintimilla (2023), because pedagogy is invested in “offering provocative questions to education” (p. 23), our work of creating bodying pedagogies cannot be created through collaging over a canvas of taken-for-granted body formations, accumulating and assimilating all perspectives on bodies, or low-stakes cross-disciplinary expansion that leaves existing knowledge silos intact. Further, strategies of knowing bodies differently by infusing novel conceptual or aesthetic additives into our existing practices of making bodies perceptible are inadequate to the proposal of creating bodying pedagogies, because these agreeable strategies traffic in what is already possible. Pedagogy, Vintimilla and Pacini-Ketchabaw (2020) assert, requires that we create “propositions and intentions that would allow for experimentation with different subjective processes and alternative futures” (p. 632). Reading pedagogy’s propositional and generative character alongside Manning’s (2014) contention that “a philosophy of the body never begins with the body: it bodies” (p. 163), it is clear that emphasizing the work of getting to know and do bodies otherwise with children is intensely pedagogical because how we propose, understand, care, and experiment with body logics and relations – and articulate a ‘philosophy of the body’ – bodies.

Over and over, creating possibilities for getting to know bodies with children takes up the work of figuring out how to live well together and, therefore, of bodying’s co-compositions with relationality, collectivity, subjectivity, and world-making. Importantly, because “pedagogy tries to unsettle practice to find (and sometimes even liberate) its creative force” (Vintimilla & Pacini-Ketchabaw, 2020, p. 631), bodying pedagogies are not contingent upon dominant habits of doing bodies in ECE, where the rational human subject is separate from and holds dominion over worldly dynamics. While bodying pedagogies are woven with our situated intentions and commitments as subjects of/with/within ECE, the status-quo constructs that ground the humanist ECE systems that pedagogy works to unsettle begin to fray. As Manning (2016) notes, “of course how the body moves has effects, and there is no end to inflections activated by tendings that include the human. It’s just that the intention is not where we usually assume it is. It is in the event” (p. 119). In our work, this means that bodying pedagogies unfold within complex, dispersed worlds; bodying does not confine itself to human bodies. Isolation is not in bodying pedagogies’ lexicon and individualistic mandates erase all that is pedagogical within bodying.

Stressing activeness and inventiveness does not absolve bodying pedagogies of engaging with conditions we inherit, marinate in, and perpetuate, but it does shift the axis of engagement from critical analysis, negation, repair, and renovation to, instead, imagining the possible but not-yet defined. As Vintimilla (2023) notes, “this subject is one who never settles for belonging and yet recognizes itself as inscribed and constituted by the politics of truth in which it lives” (p. 20). When we take bodying as an inventive event – where “the I is in movement, active in a worlding, a taking-account of the world, co-composing with movement’s inflexions, attuning to its tendencies to form” (Manning, 2014, p. 166) – crafting bodying pedagogies asks us to be profoundly unsatisfied with how existing conditions shape how we get to know bodies in ECE, and the inadequacy of extant possibilities for doing bodies drives proposals that are create yet-unknown relations with these existing conditions. Put differently, bodying pedagogies are not anchored in or bound by what already is present but do face what exists (ex, inheritances, injustices, histories, presents) as we figure out how to contend, differently and beyond convention, with this present and towards otherwise futures. Vintimilla, detailing estrangement as a pedagogical praxis, traces an “understanding of estrangement [that] is not estrangement from the world – suggestive of distance from political and worldly affairs – but estrangement for and within the world as a way of being in a space of defamiliarization that might unsettle the stagnation of routine – the repetition of ‘the world as we know it’ patterns – and propel us to think beyond the already established by presenting the world through different and unusual angles” (p. 21). Pulling this articulation of estrangement towards our thinking with bodying pedagogies, we want to do bodies differently but do not oblige future bodies to be different based on current understandings of body difference (ex. fatness, fitness, neurotypicality). Our care for doing bodying with pedagogy with children is rooted making dominant body relations and logics (and entangled subjects, knowledges, relations) unsensible, untenable, and to not acquiesce to their unlivability. This, for us, resonates with what Manning (2014) names as “body-worlding” (p. 177) – bodying pedagogies as the necessarily disorienting and persistently eventful work of figuring out how to do bodies otherwise for more livable, just, affirmative futures with bodies with children.

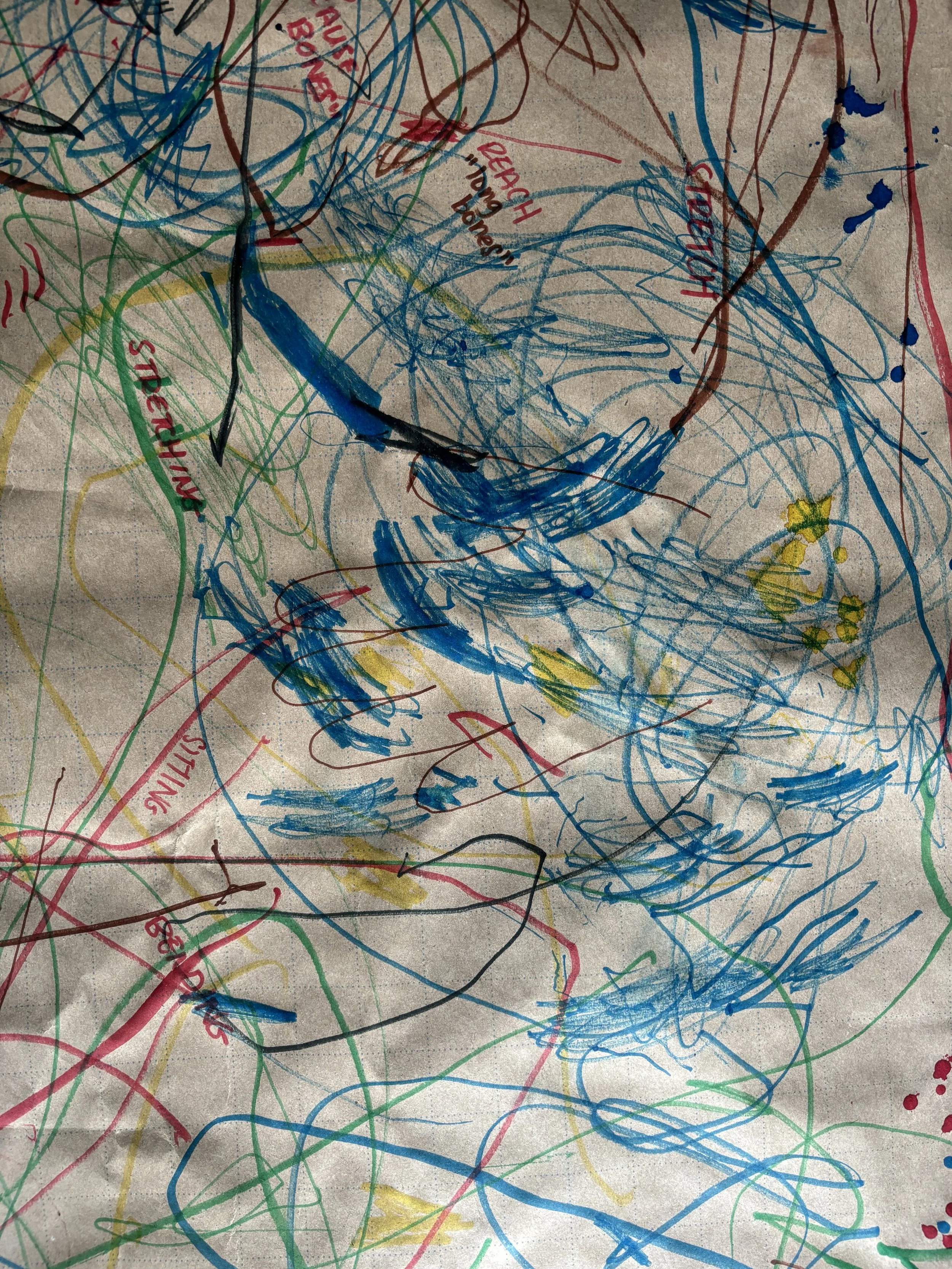

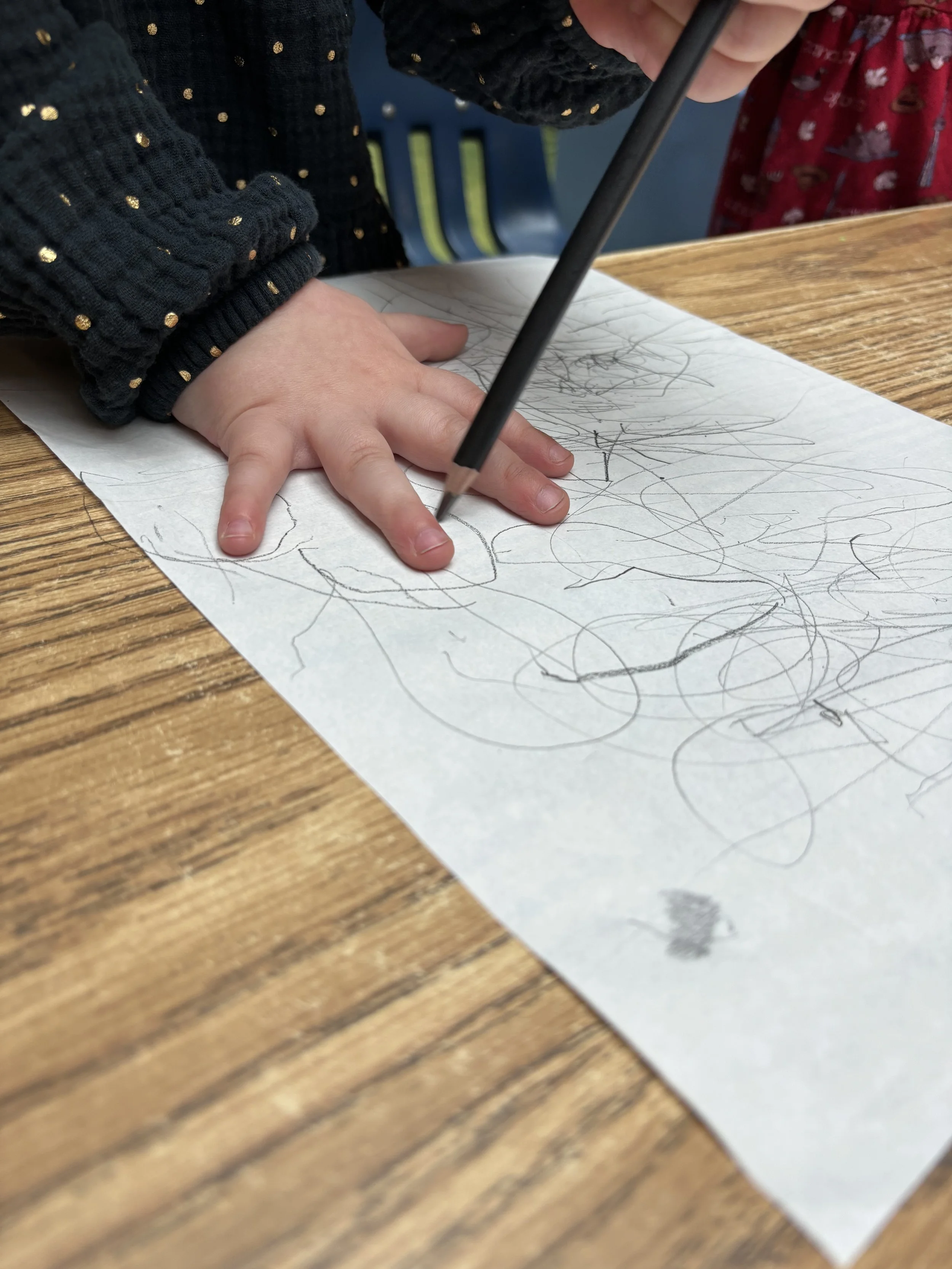

Bodying pedagogies are eventful, active, inventive and really, really difficult work. We want to make clear that, in our work, the question of how to sustain bodying pedagogies has been and remains very urgent. Our proposals towards doing bodies otherwise with children are slippery and awkward and often feel cumbersome and paltry at the same time, symptomatic of how much of what we know of bodying in ECE is in excess of available language, logics, practices, or referents. The unwieldiness of our proposals is suggestive, too, of how trained we are at wanting to ‘know’ bodies through familiar frames and processes; more than once we have found ourselves over-proposing, almost compensating or working too hard to explain an idea in a particular way. For example, many times we noticed ourselves trying to incite or speak an idea using our arms. We would gesture and wave our arms, making movement or an opening or a pathway, and then would follow that by trying to explain, in language, what we had just explained with our arms. This push to language feels intolerably insufficient and reiterates the status-quo all-too-easily, and, concurrently, makes clear that we need to invent different moves of ‘explaining’ proposals for studying and doing bodies with children.

We now share two problems/stories from our work towards bodying pedagogies: imprecise body grammars and escapable body temporalities. As we offer these two continuing propositions from our work, we emphasize that “this is movement: understanding that we are not trying to stop nor resolve a question, but rather to keep up with it as it shapes and reshapes the worlds that it meets. We understand this as the very invitation that pedagogy offers us to consider in our work” (Land & Vintimilla, 2024, p. 129). Creating bodying pedagogies requires that we keep these problems lively and return to them, often, in the context and concerns that animate our work and what we are pedagogically committed to doing otherwise in ECE in Canada.

For us, this means working with imprecise body grammars and escapable body temporalities to interrupt and re-imagine how biopedagogies, body curriculum, and normative child development tangle with how we create emplaced, fleshed, responsive, affirmative, and ever shapeshifting bodying pedagogies with children. From our discussions about biopedagogies, we carry a concern with biomorality as an arbiter of citizenship and humanness and want to think outside of the status-quo deterministic relation between body governance and neoliberal subjectivity. With Body Curriculum (Azzarito 2019a, 2019b), we pay attention to questions of making bodies visible, counter-storying bodies, and curriculum-making as a body-articulating project. Against normative child development, we take body relations of discipline, commodity, stability, consistency, endurance, investment, and futurity as inheritances that trouble and should be troubled towards more livable bodying relations. As we share our engagements with imprecise body grammars and escapable body temporalities, we hope that readers will imagine how tendrils of these stories/problems/provocations might thread through their contexts and how bodying pedagogies, as a proposal for getting to know bodies otherwise with children, might find footing in the collectives that hold ECE in Canada together.